Wampum Beads

Wampum

"Wampum are small cylindrical white or black (purple) beads, made from the white inner whorls of whelk or dark eyes of quahog shells. These beads are woven into bracelets and belts, or threaded on strings, and are used in diplomatic negotiations, as documentation of events and legal commitments, as ritual objects, and as a trade commodity. The colors and motifs woven into the belts and bracelets bear meanings: white tending to signify positive and purple signifying negative messages (or used for the creation of patterns). Wampum belts hold great spiritual importance.The Clements Library acquired the papers of Josiah Harmar in 1936. Harmar was a brigadier general in the United States Army, serving as military commander in the Northwest Territory from 1784 to 1791. The collection arrived with multiple wampum belts and strings. These wampum strings were likely manufactured by an eastern Algonquin tribe. Thank you http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/american-encounters/american-encounters6.php "

Winona, the Child-Woman

A Sioux Legend part 1 The sky is blue overhead, peeping through window-like openings in a roof of green leaves. Right between a great pine and a birch tree their soft doeskin shawls are spread, and there sit two Sioux maidens amid their fineries - variously colored porcupine quills for embroidery laid upon sheets of thin birch-bark, and moccasin tops worked in colors like autumn leaves. It is Winona and her friend Miniyata.

They have arrived at the period during which the young girl is carefully secluded from her brothers and cousins and future lovers, and retires, as it were, into the nunnery of the woods, behind a veil of thick foliage. Thus she is expected to develop fully her womanly qualities.

In meditation and solitude, entirely alone or with a chosen companion of her own sex and age, she gains a secret strength, as she studies the art of womanhood from nature herself.

Winona has the robust beauty of the wild lily of the prairie, pure and strong in her deep colors of yellow and scarlet against the savage plain and horizon, basking in the open sun like a child, yet soft and woman-like, with drooping head when observed. Both girl are beautifully robed in loose gowns of soft doeskin, girded about the waist with the usual very wide leather belt.

"Come, let us practice our sacred dance," says one to the other. Each crowns her glossy head with a wreath of wild flowers, and they dance with slow steps around the white birch, singing meanwhile the sacred songs.

Now upon the lake that stretches blue to the eastward there appears a distant canoe, a mere speck, no bigger than a bird far off against the shining sky.

"See the lifting of the paddles!" exclaims Winona.

"Like the leaping of a trout upon the water!" suggests Miniyata.

"I hope they will not discover us, yet I would like to know who they are," remarks the other, innocently.

part 2

The birch canoe approaches swiftly, with two young men plying the light cedar paddles. The girls now settle down to their needlework, quite as if they had never laughed or danced or woven garlands, bending over their embroidery in perfect silence. Surely they would not wish to attract attention, for the two sturdy young warriors have already landed.

They pick up the canoe and lay it well up on the bank, out of sight. Then one procures a strong pole. They lift a buck deer from the canoe - not a mark upon it, save for the bullet wound; the deer looks as if it were sleeping! They tie the hind legs together and the forelegs also and carry it between them on the pole.

Quickly and cleverly they do all this; and now they start forward and come unexpectedly upon the maidens' retreat! They pause for an instant in mute apology, but the girls smile their forgiveness, and the youths hurry on toward the village.

Winona has attended her first maidens' feast and is considered eligible to marriage. She may receive young men, but not in public or in a social way, for such was not the custom of the Sioux. When he speaks, she need not answer him unless she chooses.

The Indian woman in her quiet way preserves the dignity of the home. From our standpoint the white man is a law-breaker! The "Great Mystery," we say, does not adorn the woman above the man. His law is spreading horns, or flowing mane, or gorgeous plumage for the male; the female he made plain, but comely, modest and gentle.

She is the foundation of man's dignity and honor. Upon her rests the life of the home and of the family. I have often thought that there is much in this philosophy of an untutored people. Had her husband remained long enough in one place, the Indian woman, I believe, would have developed no mean civilization and culture of her own.

part 3

It was no disgrace to the chief's daughter in the old days to work with her hands. Indeed, their standard of worth was the willingness to work, but not for the sake of accumulation, only in order to give.

Winona has learned to prepare skins, to remove the hair and tan the skin of a deer so that it may be made into moccasins within three days. She has a bone tool for each stage of the conversion of the stiff raw-hide into velvety leather. She has been taught the art of painting tents and raw-hide cases, and the manufacture of garments of all kinds.

Generosity is a trait that is highly developed in the Sioux woman. She makes many moccasins and other articles of clothing for her male relatives, or for any who are not well provided. She loves to see her brother the best dressed among the young men, and the moccasins especially of a young brave are the pride of his woman-kind. Her own person is neatly attired, but ordinarily with great simplicity. Her doeskin gown has wide, flowing sleeves; the neck is low, but not so low as is the evening dress of society.

Her moccasins are plain; her leggings close-fitting and not as high as her brother's. She parts her smooth, jet-black hair in the middle and plaits it in two. In the old days she used to do it in one plait wound around with wampum. Her ornaments, sparingly worn, are beads, elks' teeth, and a touch of red paint. No feathers are worn by the woman, unless in a sacred dance. She is supposed to be always occupied with some feminine pursuit or engaged in some social affair, which also is strictly feminine as a rule.

Even her language is peculiar to her sex, some words being used by women only, while others have a feminine termination. There is an etiquette of sitting and standing, which is strictly observed. The woman must never raise her knees or cross her feet when seated. She seats herself on the ground side-wise, with both feet under her.

part 4

Notwithstanding her modesty and undemonstrative ways, there is no lack of mirth and relaxation for Winona among her girl companions.

In summer, swimming and playing in the water is a favorite amusement. She even imitates with the soles of her feet the peculiar resonant sound that the beaver makes with her large, flat tail upon the surface of the water. She is a graceful swimmer, keeping the feet together and waving them backward and forward like the tail of a fish.

Nearly all her games are different from those of the men. She has a sport of and-throwing which develops fine muscles of the shoulder and back. The wands are about eight feet long, and taper gradually from an inch and a half to half an inch in diameter. Some of them are artistically made, with heads of bone and horn, so that it is remarkable to what a distance they may be made to slide over the ground. In the feminine game of ball, which is something like "shinny," the ball is driven with curved sticks between two goals. It is played with from two to three to a hundred on a side, and a game between two bands or villages is a picturesque event.

A common indoor diversion is the "deer's foot" game, played with six deer hoofs on a string, ending in a bone or steel awl. The object is to throw it in such a way as to catch one or more hoofs on the point of the awl, a feat which requires no little dexterity. Another is played with marked plum-stones in a bowl, which are thrown like dice and count according to the side that is turned uppermost.

Winona's wooing is a typical one. As with any other people, love-making is more or less in vogue at all times of the year, but more especially at midsummer, during the characteristic reunions and festivities of that season. The young men go about usually in pairs, and the maidens do likewise. They may meet by chance at any time of day, in the woods or at the spring, but often seek to do so after dark, just outside the teepee. The girl has her companion, and he has his, for the sake of propriety or protection. The conversation is carried on in a whisper, so that even those chaperone's do not hear.

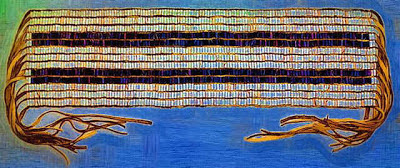

image: wampum belt by ElizabethJamesPerry

part 5

At the sound of the drum on summer evenings, dances are begun within the circular rows of teepees, but without the circle the young men promenade in p[airs. Each provides himself with the plaintive flute and plays the simple cadences of his people, while his person is completely covered with his fine robe, so that he cannot be recognized by the passerby. At every pause in the melody he gives his yodel-like love-call, to which the girls respond with their musical, sing-song laughter.

Matosapa has loved Winona since the time he saw her at the lake-side in her parlor among the pines. But he has not had much opportunity to speak until on such a night, after the dances are over. There is no outside fire; but a dim light from within the skin teepees sheds a mellow glow over the camp, mingling with the light of a young moon. Thus these lovers go about like ghosts. Matosapa had already circled the teepees with his inseparable brother-friend, Brave Elk.

"Friend, do me an honor to-night!" he exclaims, at last. "Open this first door for me, since this will be the first time I shall speak to a woman!"

"Ah," suggests Brave Elk, "I hope you have selected a girl whose grandmother has no cross dogs!"

"The prize that is won at great risk is usually valued most," replies Matosapa.

"Ho, kola! I shall touch the door-flap as softly as the swallow alights upon her nest. But I warn you, do not let your heart beat too loudly, for the old woman's ears are still good!"

So, joking and laughing, they proceed toward a large buffalo tent with a horse's tail suspended from the highest pole to indicate the rank of the owner. They have ceased to blow the flute some paces back, and walk noiselessly as a panther in quest of a doe.

image: Wampum wrist treaty (worn ornament), probably Iroquois, 18th_century - Native American collection - Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

part 6

Brave Elk opens the door. Matosapa enters the tent. As was the wont of the Sioux, the well-born maid has a little teepee within a teepee - a private apartment of her own. He passes the sleeping family to this inner shrine. There he gently wakens Winona with proper apologies. This is not unusual or strange to her innocence, for it was the custom of the people. He sits at the door, while his friend waits outside, and tells his love in a whisper.

To this she does not reply at once; even if she loves him, it is proper that she should be silent. The lover does not know whether he is favorably received or not, upon this his first visit. He must now seek her outside upon every favorable occasion. No gifts are offered at this stage of the affair; the trafficking in ponies and "buying" a wife is entirely a modern custom.

Matosapa has improved every opportunity, until Winona has at last shyly admitted her willingness to listen. For a whole year he has been compelled at intervals to repeat the story of his love. Through the autumn hunting of the buffalo and the long, cold winter he ofter presents her kinsfolk with his game.

At the nest midsummer the parents on both sides are made acquainted with the betrothal, and they at once begin preparations for the coming wedding. Provisions and delicacies of all kinds are laid aside for a feast. Matosapa's sisters and his girl cousins are told of the approaching event, and they too prepare for it, since it is their duty to dress or adorn the bride with garments made by their own hands.

part 7

With the Sioux of the old days, the great natural crises of human life, marriage and birth, were considered sacred and hedged about with great privacy. Therefore the union is publicly celebrated after and not before its consummation. Suddenly the young couple disappear. They go out into the wilderness together, and spend some days or weeks away from the camp. This is their honeymoon, away from all curious or prying eyes. In due time they quietly return, he to his home and she to hers, and now at last the marriage is announced and invitations are given to the feast.

The bride is ceremoniously delivered to her husband's people, together with presents of rich clothing collected from all her clan, which she afterward distributes among her new relations. Winona is carried in a travois handsomely decorated, and is received with equal ceremony. For several days following she is dressed and painted by the female relatives of the groom, each in her turn, while in both clans the wedding feast is celebrated.

To illustrate womanly nobility of nature, let me tell the story of Dowanhotaninwin, Her-Singing-Heard. The maiden was deprived of both father and mother when scarcely ten years old, by an attack of the Sacs and Foxes while they were on a hunting expedition. Left alone with her grandmother, she was carefully reared and trained by this sage of the wild life.

Nature had given her more than her share of attractiveness, and she was womanly and winning as she was handsome. Yet she remained unmarried for nearly thirty years - a most unusual thing among us; and although she had worthy suitors in every branch of the Sioux nation, she quietly refused every offer.

Certain warriors who had distinguished themselves against the particular tribe who had made her an orphan, persistently sought her hand in marriage, but failed utterly. One summer the Sioux and the Sacs and Foxes were brought together under a flag of truce by the Commissioners of the Great White Father, for the purpose of making a treaty with them. During the short period of friendly intercourse and social dance and feast, a noble warrior of the enemy's tribe courted Dowanhotaninwin.

Image: quahog shells for wampum beads

part 8

Several of her old lovers were vying with one another to win her at the same time, that she might have inter-tribal celebration of her wedding. Behold! - the maiden accepted the foe of her childhood - one of those who had cruelly deprived her of her parents! By night she fled to the Sac and Fox camp with her lover. It seemed at first an insult to the Sioux, and there was almost an outbreak among the young men of the tribe, who were barely restrained by their respect for the Commissioners of the Great Father. But her aged grandfather explained the matter publicly in this fashion: "Young men, hear ye! Your

hearts are strong; let them not be troubled by the act of a young woman. She deprecates all tribal warfare. Her young heart never forgot its early sorrow; yet she has never blamed the Sacs and Foxes or held them responsible for the deed. She blames rather the customs of war among us. She believes in the formation of a blood brotherhood strong enough to prevent all this cruel and useless enmity. This was her high purpose, and to this end she reserved her hand. Forgive her, forgive her, I pray!"

In the morning there was a great commotion. The herald of the Sacs and Foxes entered the Sioux camp, attired in ceremonial garb and bearing in one hand an American flag and in the other a peace-pipe. He made the rounds singing a peace song, and delivering to all an invitation to attend the wedding feast of Dowanhotaninwin and their chief's son. Thus all was well. The simplicity, high purpose, and bravery of the girl won the hearts of the two tribes, and as long as she lived she was able to keep the peace between them.

The end.

Thank you Relatives at http://www.littlewolfrun.net/Sioux3.html. It was difficult to read so we brought this story to share with others over here. We bow and in gratitude in the sharing of Lakota Stories. You can read lots more over at Little Wolf Run site. Pilamayeye (Thank you in Lakota).

The Two Row Wampum Belt

“Boat and canoe” navigation metaphor as being the guiding spirit of all subsequent treaties (agreements). The paddling down the river, presents itself as a political history of the community that incorporates the involvement in the alliance known as the Seven Nations of Canada within a distinctly “Iroquois” identity paradigm (representing united nations). This is also the basis for the Declaration of Independence written by the United States of America, brotherhood, equality and freedom for all men. In God we trust, "the voice of each other". When we flow from the blue road (blue strip, virtues) to the red road (blue strip, true blue) and back (all lives in heavenly bodies of the blue oceans of time, the crystalline stone river flows elliptical paths known as hoops, circles and rings). To and fro we go, then the third yellow road appears (middle white row, where light is the glow). Five rows represent the blue, the relatives who are true. This is also expressed in the Jewish Tsitsihar or tassels on the Prayer Cloth. This is the shape (belt or sash) of a prayer cloth, four directions (green fields) and five streams (relatives beam), equals the rolling over (bows), the force and power of love that binds our hearts together. The dream appears on the yellow road and golden fields of brotherhood would run near. It's only now, we are ready to receive knowledge from each other, the ark of the covenant (boat and canoe navigation, and how to paddle down the river of), the Rainbow Clan. White Buffalo Calf Woman shares.

posted for White Buffalo Calf Woman knews and visions circle read here:

Image: pipestemwampumPipe Stem with Wampum

Date: 1800–1825

Geography: United States, Eastern Plains or Western Great Lakes

Culture: Eastern Plains or Western Great Lakes

Medium: Wood, ivory-billed woodpecker scalp, wood duck and downy feathers, horsehair, deer hair, porcupine quills, two types of bast fiber cord, cotton fabric, twill-woven wool tape, silk ribbon, shell beads (channeled whelk)

Dimensions: Length: 35 7/8 in. (91.1 cm)

Classification: Wood-Implements

Credit Line: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Hardvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Gift of the Heirs of David Kimball, 1899 (99-12-10/53110.2)

Both traditional materials and those introduced through trade with Euro-Americans are featured on this elaborate pipe stem. Attached to the front portion of the stem is the scalp of an ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird widely associated with warfare in the Plains and Woodlands regions. Plaited porcupine quillwork with hourglass designs—combined with silk, cotton, and wool fabrics acquired in trade—serves as a wrapping. Five strands of wampum (white shell beads), symbols of peace to Indian nations, hang from the ends.

Wampum Belt Make Peace Not War, the Treaty (alignment)

I Hear You as I Take an Oath

https://www.facebook.com/groups/whitebuffalocalfwoman/permalink/786050861500172/

Wampum Belt is a representative of the sacred oath, to bring heaven to earth, we as falling stars gift our hearts to the world. We send peaceful relations and harmonic vibrations.

The wampum belt signifies a treaty, an agreement to be honored. Let us sing for our family around the world as they climb to become stars all aligned together we are sown, like diamonds on the ground, we bring home a good sound. Hear our pound.

(ghost singing begins) I Hear You as I Take an Oath

I can hear you. I can feel it deep. You are trying to bring your cries to the steep. Come a running to bring flooding we care. All of those tears, ready to glare. Shine like diamonds rainbows in the end. Shine like diamonds we will be more friends. Shine like diamonds, we will have no enemy. Shine like diamonds, we shall set the sea.

Tender is the heartbeat, I can agree to this signal in time. All I can hear is the sacred rhythm and rhyme. My heart is a temple, where I share your love. You are making me listen, tighter, tighter than doves. My love is falling down to be near you. I can hear you. I can feel you.

With this wampum, my soul is riding free. I can take this agreement to last eternally. I will ride like diamonds in the sacred sky. I will cry forever to hear of this wide. You and me together you sea when visions come to you. I and you and me is true, when visions come shining through. We are three, the children knows thee, the heart of all we laugh. We are the oath of the gospel in our souls. We are proud to call you relations out loud.

I can hear you. I can feel you true. I can feel the defiling coming out of this knews. I can tell you, what you wanted to know. Yet if you do not reason with your heartbeat, you lose your gospel soul. Sing for this freedom to let us ring. Sing for the heart of your running free. Shine it all true for every single one, the little, the middle the grand and the high sun. We are together. All of us this wave. I can hear you. Do you want to be saved? I can tell you, which way to flow. Yet you must take up this hand of prayer as you go.

White Buffalo Calf Woman sings and Holiness David Running Eagle Shooting Star drums for all of the children of the Rainbows. Thank you Rainbow Mothers, Golden Fathers, Grandmother Gray, Grandfather White. And Great Spirits we rise up after we bow to everyone! Risen suns.

Gifted by Alightfromwithin.org Angel Services Around the World

Sioux Task Force and Rainbow Warriors of Prophecy

Jews for the Ark of the Covenant, the Rainbow Promise

image: wampum belt

Wampum Belt post in Crystal Indigo Children circle

11:52am Aug 30, 2014

Whitebuffalocalfwoman Twindeermother

Sister Missy Leigh Mahaney,

This is a wampum belt. Native Americans, Catholic Priests and the United States of America foundation (declaration of independence) would use for honorary collar, written devotion, an agreement or treaty. A time of negotiations and the true exchange of ideals. This was is the way to Brotherhood. This signifies an oath to flow the true way pure of heart like stars (Grandfather 15 white star teaches the humble bow) in each of us.

Your image is earth view. These images are dark blue and white heaven view. But if you look down from heaven you see stars 15 then sky blue 10 then dark blue 5. They all align. And tell the same story but down the trail, as if looking sideways again

Your devoted Sister,

Pte San Win Wbcw elder christal child of the most radiant rainbow clan, I bow to all the stars, you my family.

Image: Wampum (Quahog) Shell Tube Beads

11:09am Aug 30, 2014

Whitebuffalocalfwoman Twindeermother

Sister Missy Leigh Mahaney, this is what I see as you often dream of spacial fields. Dark blue 5 is the oceans of me and you, the below where water gathers. Sky blue 10 is the skies of you and me, the above where water gathers. Connecting the lower and upper is the Magenta 9Rainbow Bridge. From the sky blue 10 falling down from clouds water and color/ fire (appears rainbow bridge) where paradise of Magenta flows into the dark blue oceans. This is where angels sing in waves or freqencies, the middle line between dark blue and sky blue. Usually this image is from top looking down, but your image is looking sideways like you are lying down. A woman lies down to show the field, ripe to grow and sow.

Your devoted Sister, Pte San Win Wbcw elder crystal child

Daniel Torres 1:51pm Aug 29, 2014

Light and lack of light, consciousness and lack of consciousness

Missy Leigh Melissa Leigh Mahaney

yes it was dark blue and light blue that was wired.

Melanie Valerio Meris 6:02pm Aug 27, 2014

Yin-Yang...Balance

Missy Leigh Mahaney 5:56pm Aug 27, 2014

I saw this image in my mind and I wonder what is symbol of?

The Two Row Wampum is one of the oldest treaty relationships between the Onkwehonweh (original people) of Turtle Island (North America) and European immigrants. The treaty was made in 1613 between the Dutch and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) as Dutch traders and settlers moved up the Hudson River into Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory. The Dutch initially proposed a patriarchal relationship with themselves as fathers and the Haudenosaunee people as children. According to Kanien’kehá:ka historian Ray Fadden, the Haudenosaunee rejected this notion and instead proposed:

“We will not be like Father and Son, but like Brothers. [Our treaties] symbolize two paths or two vessels, travelling down the same river together. One, a birchbark canoe, will be for the Indian People, their laws, their customs, and their ways. The other, a ship, will be for the white people and their laws, their customs, and their ways. We shall each travel the river together, side by side, but in our own boat. Neither of us will make compulsory laws nor interfere in the internal affairs of the other. Neither of us will try to steer the other’s vessel.”

Well aware of the political and military strength of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (which included the Kanien’kehá:ka), the Dutch agreed with the principles of the Two Row. As was their custom for recording events of significance, the Haudenosaunee created a wampum belt out of purple and white quahog shells to commemorate the agreement. John Borrows, an Indigenous legal scholar and the author of Canada’s Indigenous Constitution, describes the physical nature of the Two Row Wampum as follows:

“The belt consists of two rows of purple wampum beads on a white background. Three rows of white beads symbolizing peace, friendship, and respect separate the two purple rows. The two purple rows symbolize two paths or two vessels travelling down the same river. One row symbolizes the Haudenosaunee people with their law and customs, while the other row symbolizes European laws and customs. As nations move together side-by-side on the River of Life, they are to avoid overlapping or interfering with one another.”

The Two Row Wampum treaty made with the Dutch became the basis for all future Haudenosaunee relationships with European powers. The principles of the Two Row were consistently restated by Haudenosaunee spokespeople and were extended to relationships with the French, British, and Americans under the framework of the Silver Covenant Chain agreements. It was understood by the Haudenosaunee that the Two Row agreement would last forever, that is, “as long as the grass is green, as long as the water flows downhill, and as long as the sun rises in the east and sets in the west.”

While 2013 marked the 400th anniversary of the introduction of the Two Row to Europeans, it is important to note that the concept of the Two Row, based on reciprocal relationships of peace, friendship, and respect, has a much deeper meaning to the Haudenosaunee.

The Two Row is a foundational philosophical principle, a universal relationship of non-domination, balance, and harmony between different forces. The Two Row principles of peace, respect, and friendship can exist within any relationship between autonomous beings working in concert. These include nation-to-nation relationships, dynamics between lovers and partners, and the relationship between human beings and our environment.

While the Two Row Wampum was created to commemorate the introduction of the Dutch to the continent and is derived from Haudenosaunee traditions and philosophy, it is also consistent with the outlooks of many other Indigenous peoples seeking to accommodate themselves to the sudden arrival of Europeans on Turtle Island. Almost universally, Indigenous peoples extended their hands in peace and friendship to the settlers on their lands and sought to improve their lives through trade and exchange with the newcomers. But at the same time, Indigenous peoples were intent on maintaining their own ways of life.

The Two Row can function as a framework for decolonization right across Turtle Island, since holding true to the Two Row means supporting the right of Onkwehonweh people to maintain themselves on their own land bases according to their own systems of self-governance, organization, and economics. (Rather than being driven by profitability and production for markets, most traditional Indigenous economies were based upon localized subsistence.)

In this framework people do not own land but belong to the land as a part of creation and they safeguard it on behalf of coming generations. Before European contact, resources and wealth were shared in most Indigenous societies, and production was geared toward meeting human needs rather than the manufacture of commodities to be bought and sold on the market.

The Two Row Wampum remains a treaty relationship that Haudenosaunee and other Indigenous nations defend today, even if the Canadian state has failed to uphold the principles of the treaties it inherited from the British Crown. We should not be surprised that the British Crown and the colonial Canadian state have been unwilling to respect the self-determination of Indigenous peoples or to uphold the Two Row Wampum. Still, non-Indigenous people can learn this history and inform others about the original framework based on genuine peace, respect, and friendship with Indigenous peoples.

With the rise of a new cycle of Indigenous struggles, and with the global crisis of capitalism intensifying, the recent 400th anniversary of the Two Row Wampum is a good moment for us to start redefining the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Article abridged and adapted from the Two Row Times.

Tom Keefer was a founding editor of Upping the Anti and is the general manager of the Two Row Times.Tags: environment, government, settler colonialism, treaties 18 This article appeared in the March/April 2014 issue of Briarpatch.

Spanish Pillar Dollar image (not shown)

"Minted in Mexico in 1746, this coin is an example of the famous "pillar dollars" (or pieces of eight) that were used so extensively during colonial and post-colonial periods in American history. Image courtesy of EarlyAmerican.com."

The story of American money began more than three centuries ago. The early settlers of New England relied heavily upon foreign coins for conducting their day to day business affairs. At any given time, coins from Europe, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere could be found in circulation.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

Image shown: Wampum money from colonial times

"In the absence of circulating coinage, wampum was used in the northeastern colonies as substitute money, giving rise to the current slang "shelling out". In 1611, the Huron people presented the wampum belt shown above to Samuel de Champlain, the governor of the French colony of Quebec. Image courtesy of Inquiry Unlimited."

The Spanish milled dollar and its fractional parts were the principal coins of the American colonists, and served as the model for our silver dollar and its sub-divisions in later years.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

(image not shown) William Penn treaty

As a barter medium, wampum was a key interaction object between Euro-American settlers and the Native American culture. In the scene above, William Penn (center) is purchasing land from the Delaware tribe in 1682 that became the colony of Pennsylvania. As part of the payment, Penn provided wampum beads. Image courtesy of Library of Congress

We suggest that anyone wishing to engage in a comprehensive study of American money from the earliest days of wampum and beaver pelts to the present day should obtain a copy of America's Money, America's Story, by Richard Doty (update: see below)

To be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story. If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to the "Coins & US History" section.

Thank you http://www.us-coin-values-advisor.com/colonial-times.html

The story of American money began more than

three centuries ago. The

early settlers of New England relied heavily upon foreign coins for

conducting their day to day business affairs. At any given time, coins

from Europe, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere could be found in

circulation. - See more at: http://www.us-coin-values-advisor.com/colonial-times.html#sthash.n7iB80xh.dpuf

The Beginning of

American Money

The Beginning of

American Money

| Minted in Mexico in 1746, this coin is an example of the famous "pillar dollars" (or pieces of eight) that were used so extensively during colonial and post-colonial periods in American history. Image courtesy of EarlyAmerican.com. |

The story of American money began more than

three centuries ago. The

early settlers of New England relied heavily upon foreign coins for

conducting their day to day business affairs. At any given time, coins

from Europe, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere could be found in

circulation.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

| In the absence of circulating coinage, wampum was used in the northeastern colonies as substitute money, giving rise to the current slang "shelling out". In 1611, the Huron people presented the wampum belt shown above to Samuel de Champlain, the governor of the French colony of Quebec. Image courtesy of Inquiry Unlimited. |

The Spanish milled dollar and its fractional

parts were the principal

coins of the American colonists, and served as the model for our silver

dollar and its sub-divisions in later years.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

| As a barter medium, wampum was a key interaction object between Euro-American settlers and the Native American culture. In the scene above, William Penn (center) is purchasing land from the Delaware tribe in 1682 that became the colony of Pennsylvania. As part of the payment, Penn provided wampum beads. Image courtesy of Library of Congress |

We suggest that anyone wishing to engage in a

comprehensive study of

American money from the earliest days of wampum and beaver pelts to the

present day should obtain a copy of America's Money, America's Story,

by Richard Doty

(update: see below)

To be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story .

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

.

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

- See more at: http://www.us-coin-values-advisor.com/colonial-times.html#sthash.n7iB80xh.dpufTo be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story

The Beginning of

American Money

| Minted in Mexico in 1746, this coin is an example of the famous "pillar dollars" (or pieces of eight) that were used so extensively during colonial and post-colonial periods in American history. Image courtesy of EarlyAmerican.com. |

The story of American money began more than

three centuries ago. The

early settlers of New England relied heavily upon foreign coins for

conducting their day to day business affairs. At any given time, coins

from Europe, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere could be found in

circulation.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

| In the absence of circulating coinage, wampum was used in the northeastern colonies as substitute money, giving rise to the current slang "shelling out". In 1611, the Huron people presented the wampum belt shown above to Samuel de Champlain, the governor of the French colony of Quebec. Image courtesy of Inquiry Unlimited. |

The Spanish milled dollar and its fractional

parts were the principal

coins of the American colonists, and served as the model for our silver

dollar and its sub-divisions in later years.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

| As a barter medium, wampum was a key interaction object between Euro-American settlers and the Native American culture. In the scene above, William Penn (center) is purchasing land from the Delaware tribe in 1682 that became the colony of Pennsylvania. As part of the payment, Penn provided wampum beads. Image courtesy of Library of Congress |

We suggest that anyone wishing to engage in a

comprehensive study of

American money from the earliest days of wampum and beaver pelts to the

present day should obtain a copy of America's Money, America's Story,

by Richard Doty

(update: see below)

To be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story .

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

.

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

- See more at: http://www.us-coin-values-advisor.com/colonial-times.html#sthash.n7iB80xh.dpufTo be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story

he story of American money began more than

three centuries ago. The

early settlers of New England relied heavily upon foreign coins for

conducting their day to day business affairs. At any given time, coins

from Europe, Mexico, South America, and elsewhere could be found in

circulation.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

Of special importance were the coins that migrated to the colonies from Spanish possessions in the New World. Included in these were the Spanish milled dollar and the doubloons (worth about $16). The Spanish milled dollar, also called the "piece of eight" or the "pillar dollar" (because of the pillars flanking the globes) was the equivalent of eight Spanish reales. One real equaled 12.5 cents and was known as a "bit". Thus a quarter came to be known as "two bits", an expression still used today.

In December 2003, perhaps the foremost authoritative reference ever on Spanish mints in the New World, Cobs Pieces of Eight and Treasure Coins: The Early Spanish American Mints and Their Coinages, 1536-1773, was published. Containing over 2000 photos, this work will provide historical background essential to understanding 250 years of Spanish history in the Americas.

| In the absence of circulating coinage, wampum was used in the northeastern colonies as substitute money, giving rise to the current slang "shelling out". In 1611, the Huron people presented the wampum belt shown above to Samuel de Champlain, the governor of the French colony of Quebec. Image courtesy of Inquiry Unlimited. |

The Spanish milled dollar and its fractional

parts were the principal

coins of the American colonists, and served as the model for our silver

dollar and its sub-divisions in later years.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

For the most part, however, much larger quantities of coins were needed. Because of the scarcity of coins, especially in the more remote areas, the colonists sometimes used other mediums of exchange, such as bullets, tobacco, animal skins, and very importantly, strung-together mussel shells called wampum.

Wampum was made from hard-shelled clams, usually the Northern Quahog (purple) and Atlantic Whelk (white), broken up into small beads, polished, drilled through lengthwise, and then strung together. Native Americans were the first makers of wampum. The difficulty in producing the strings, and their resultant beauty, is what gave wampum intrinsic value.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, exchange rates for white wampum were set: 360 beads = 5 shillings; 6 beads = 1 penny. Purple wampum, less abundant in nature, was worth at least twice as much as the white. Some of the things you could use wampum for as legal tender included taxes due to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, tuition at Harvard University, and passage on the Brooklyn Ferry. As the 19th century progressed, wampum became less important for barter, but it wasn't until around 1890 that the last wampum mill shut down.

| As a barter medium, wampum was a key interaction object between Euro-American settlers and the Native American culture. In the scene above, William Penn (center) is purchasing land from the Delaware tribe in 1682 that became the colony of Pennsylvania. As part of the payment, Penn provided wampum beads. Image courtesy of Library of Congress |

We suggest that anyone wishing to engage in a

comprehensive study of

American money from the earliest days of wampum and beaver pelts to the

present day should obtain a copy of America's Money, America's Story,

by Richard Doty

(update: see below)

To be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story .

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

.

If it's anything like the original in terms of content, then it just

has to be one of the best friends a numismatic researcher could ever

hope to have. One of these days, when we get back to adding chapters to

the "Coins & US History" section, Doty's new book gets the "Buy

Now" click at Amazon from us.

- See more at: http://www.us-coin-values-advisor.com/colonial-times.html#sthash.n7iB80xh.dpufTo be honest, Doty's approach to the subject is quite dry, and is best suited to the scholarly type. That being said, he does a great job placing the story of America's money in historical and cultural context. Our monetary system evolved as our experience as a nation grew; money changed and stabilized as we developed from a struggling nation into the world's lone superpower.

In 2008, Doty published a new version of America's Money - America's Story

Image: Hawkeye's Wampum Sash, Chingachgook's Wampum Choker, and Wampum

There is a place where the Buffalo (flesh of earth, the light that grows, the four sacred directions, where we do) roam, and my heart does know how to roam, to be across the rolling hills, to eat of the green grass and know my fills. I am nourished by this love, the place, where I live inside the dark, the heaven calling, to fill me up. We the Rainbow Clan do know (how to drink from this spiritual cup), that we are part of this sacred show, where the Horse (soul of heaven, the heart that knows) runs wild and free, to be with Warriors, the Dog (rainbow warrior of prophecy who stands their ground) who bleeds (follows the red road, the law of love, where the fighting is for the unification of the broken heart, to bring the warrior up).

Gifted by Alightfromwithin.org Angel Services Around the World

Sioux Task Force and Rainbow Warriors of Prophecy

Jews for the Ark of the Covenant, the Rainbow Promise

.jpg)

BlossomingDeerPetals(Red)BlueLakePeopleLeadingMigration.jpg)